The weather brief at 0745 indicated good conditions over Larsen B sites, but deteriorating conditions at Rothera. We were assigned helper John Eager and chief pilot Alan Meredith. Alan said we needed to return by 1700. Did rush job to get dressed, load all equipment (so we could work at any of the five sites) and make three lunches for Malcy, John, and me. In my haste, I left the Canon camera in the Old Bransfield dressing room.

While I was making sandwiches in the kitchen at 0855, a PA announcement asked if anyone had seen Terry. I called Ops and said I was almost done. I rushed outside just as Clem pulled up on a Gator to drive me to the Twin Otter. The wind was already rising and the clouds were moving in. I hopped into the plane, with Malcy in the co-pilot’s seat, John behind him, and me behind John. Malcy told me we were going just to Flask not Scar Inlet nor anywhere else. We took off at 0910.

After 20 minutes, we had clearing to the west and clouds to the east. Another 20 minutes and it was all clouds. Then over the divide east of Larsen C, we had clouds to the west and clear skies to east all the way to Upper Leppard Glacier and Flask Glacier, whose fjord we entered at the AMIGOS-3 location, which I spotted out the window.

I undid my seat belt, stuck my head in the cockpit, and told Alan we were at AMIGOS-3 not cGPS FLSK. Apparently Andy had given him the wrong coordinates. I told him (which of course involves yelling to be heard above the roar of the engines) that we needed to go farther upstream which we did.

After a few minutes we spotted a solar panel installation, made a touch and go pass, and then landed. I remarked that the bottom of the panel was well above the snow, so it didn’t need to be raised. We unloaded all our equipment, I took some photos, and we started digging and immediately encountered an ice layer. We managed to get through the ice and exposed the top of a metal box.

It didn’t look like the top of the gray Hardig enclosure I was expecting. Malcy asked what was in the box, and I joked that maybe it contained whiskey. Then I noticed that the weather sensor was missing and must have blown off, and then that the antenna was mounted with the solar panel instead of separately, and then that the panel was too small, and then I said, “This is the wrong GPS system.”

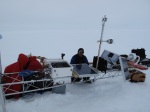

Malcolm Airey standing next to what should have been cGPS FLSK but was actually a GPS that Daniel Farinotti needs to inspect and collect data from.

I’m not sure it was the most embarrassing moment in my life, but it ranks right up there with pooping in my pants during class in the second grade. My coworkers were a bit peeved to have spent half an hour vandalizing someone else’s GPS, but they seemed to have taken it in stride. God (or maybe just Google) only knows what they said behind my back. So we piled ourselves and our equipment back into the plane and I provided Alan with the correct coordinates. He said it was another 2.9 miles up the fjord so off we went.

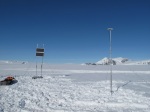

A few minutes later we located the correct site, made another touch and go pass, and landed at about 1115 Rothera Time (RT), about one hour after our first landing. Again we unloaded everything and I took some pictures. The bottom of the solar panel was 50 centimeters above the snow surface, which, if we’d had more time, would have indicated that we needed to raise the panel.

Alan had told us we needed to leave in three hours, and since I knew I had to replace the electronics at this site, I decided we would not raise the panel. We started digging, and again struck some ice, enough that Malcy need an ice axe to get through it, particularly a layer directly under the panel. We quickly reached the top of the enclosure less than a meter below the snow surface. After another 20 minutes, we had cleared a shovel width around the enclosure down to a depth about two inches below the bottom of the lid.

I took photos, and we undid the latches and raised the lid at 1217 RT. I took photos of the electronics inside. I could see the leftmost two LEDs were off, the next two were flashing, and the rightmost two were lit steady which I believe indicated that the system was still recording data, but just not able to send it back to Boulder. Continuing the detailed instructions I’d received from Seth White of UNAVCO, I powered down the receiver, and then turned off the three power circuit breakers. I asked the other three team members to swap out the WXT520 weather station while I swapped out the Iridium modem and the Trimble GPS receiver.

Once we had completed all the equipment swaps, I took more photos, powered up the circuit breakers, and then made the first call to Seth at 1345 RT. He told me to latch up the box, he would run some tests, and to call him back in 10 minutes. When I called him back, he said that FLSK had answered the phone, but he couldn’t connect, so he had me unlatch and reopen the box, and start inspecting the wiring. I also told him I could only see one green LED lit. After a minute or two talking to him, I noticed that I hadn’t reconnected pin 2 on the timer circuit after disconnecting it in order to reroute the pin 1 and pin 3 connections. I reconnected pin 2, and Seth was then able to disconnect. I told him I could still only see one green LED, which puzzled him until I realized I was still wearing my sunglasses. I took them off, and then saw the same pattern I saw when I first opened the box. He said everything now looked good to him, so we closed up the box again and loaded up the plane.

Large open crevasses near the Flask Glacier grounding line about half way between AMIGOS-3 and AMIGOS-4.

I asked Alan if we’d have time to fly over Scar Inlet to see inspect the crevasse situation, and he said we did. I asked Malcy if I could sit in the co-pilots seat this trip, and we took off at 1430 RT. We again made a pass over AMIGOS-3 and I took some photos, one of which actually came out (barely). We flew over the heavily crevassed region of Flask Glacier downstream of AMIGOS-3, and found AMIGOS-4 on Scar Inlet about five minutes later at about 1445 RT. We made a pass around the station and this time I got better photos. Alan said that the crevasses around the station precluded landing nearby, but he didn’t see any problems landing off a kilometer or so to the east as Steve King had done last year with Ted Scambos.

I then gave Alan the cGPS LPRD coordinates (easier to do with the headset on). I didn’t get any photos but I could easily see that the snow level is up to the bottom of the solar panels, so we’ll need to raise them, probably by just extending the existing splints. And we should have time to do this since I don’t have to swap out any electronics, just upgrade the firmware and the configuration. We then left at about 1500 Rothera time or so.

Weather in Rothera was considerably worse than we had left. We landed at 1620 Rothera time under a 500-1000 foot ceiling into a northerly 25-30 knot wind and moderate snow. Andy B acknowledged a minor share of culpability for the cGPS error, and said that he had since rechecked all of our other four locations that he had given the pilots and they all looked good. Took lots of appropriate but gentle ribbing at dinner about my error earlier in the day. Turns out that the mistaken GPS was one of the units that Daniel needs to visit to collect data, so the fact that we uncovered it was not a wasted effort.

Was too nervous about the presidential elections to head to the bar and spent the evening downloading exit poll results. Most of the polls were still open when I went to bed around 2200 RT and there weren’t many real results available yet. Note that with the end of daylight savings in the states, MST is now four hours behind Rothera time, which in turn is three hours behind Coordinated Universal Time (UTC).